I've spent the last two days in the State Library working on my next essay, which will be on the impact of the telegraph on foreign news reportage in

The Times. I've been reading about carrier-pigeons, morse-code, all kinds of interesting stuff. I could easily research an essay on Julius Reuter alone.

Yesterday I introduced a friend to Spicy Fish. She ordered the chicken with chilli, while I had the stewed chicken in spring onion sauce, which is my current favourite. Sure enough, as predicted in previous posts, someone at an adjacent table ordered the trademark spicy fish. Today I wandered around looking for somewhere to have lunch, and found a Japanese place on Russell Street. I'm annoyed with myself that I forgot to take note of the name. I had chicken okonomiyaki, which

apparently translates to "cook what you like, the way you like".

Whilst at the Library, a guy sitting two corrals away from me - who had been sitting there all day as I had - had his laptop stolen. He came back from looking up a book, and realised his laptop was gone! He asked me if I'd seen anything, which I hadn't. He was gutted, as you could imagine. Poor guy.

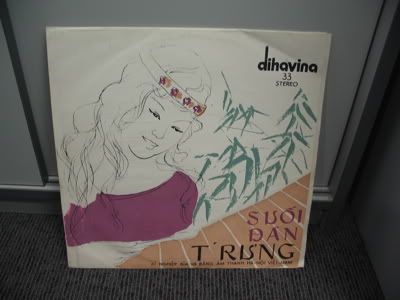

One book I was reading today was H. Simonis'

The Street of Ink: An Intimate History of Journalism. Simonis was an English journalist in the late nineteenth century. He proclaims that nobody knows the history of

The Times better than he, with the exception of Lord Northcliffe, who was still alive at the time of writing. The State Library's copy is from 1917, and is correspondingly charismatic, as old books tend to be. I enjoyed this observation on Lord Northcliffe's personality;

(Simonis has just described Lord Northcliffe's ability to succinctly summarise a person's character in a few words)... This gift of diagnosing character, so to speak, is allied to an extraordinary memory. I have rarely met a man who remembers facts and faces so well. Lord Northcliffe has, indeed, a remarkable equipment of strength of mind and manner which gives to his personality a wonderful charm. As he uses his memory for facts and figures in his daily work, so he uses his memory for faces and conversation in the exercise of a supreme tact that conveys to one whom he has met before a gratifying sensation of having left an agreeable impression. This is heightened by the way in which he devotes his whole attention to the subject he discusses, whether it is personal or otherwise. For the moment he locks every compartment of his brain save one which he uses for the time being. When you have gone, he will lock this, too, and open another. If, in the course of conversation, you ask him a question, there is another mental pigeon-hole fully stored with all the information you want. Never, apparently, could there be a mind better equipped for its special needs and more methodically ordered than his.

I have met people like this, and sometimes wish I could be more like it myself - people who

remember things about you, and even though you've only met them once, they follow-up on things you told them about yourself last time you met.

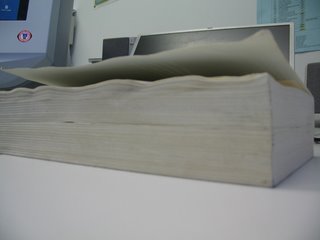

One of the books, Daniel J. Boorstin's The Creators, had significant water-damage on the last 100 pages.

One of the books, Daniel J. Boorstin's The Creators, had significant water-damage on the last 100 pages.

This wasn't mentioned in the book's description, and although the book was a bargain, I still feel a tad ripped-off. It's always difficult to know what to do in these situations. One one hand, I want the seller to be aware that the book's condition wasn't described adequately, but on the other, I don't want a refund, as I want to keep the book.

UPDATE: I just opened J. R. Hale's Renaissance Europe 1480-1520 and heard (and felt) the spine crack as I did so. This will mean that the pages will eventually start falling out. It's a 1971 paperback, so it's not unexpected.

This wasn't mentioned in the book's description, and although the book was a bargain, I still feel a tad ripped-off. It's always difficult to know what to do in these situations. One one hand, I want the seller to be aware that the book's condition wasn't described adequately, but on the other, I don't want a refund, as I want to keep the book.

UPDATE: I just opened J. R. Hale's Renaissance Europe 1480-1520 and heard (and felt) the spine crack as I did so. This will mean that the pages will eventually start falling out. It's a 1971 paperback, so it's not unexpected.

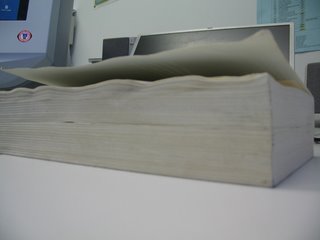

One of the books, Daniel J. Boorstin's The Creators, had significant water-damage on the last 100 pages.

One of the books, Daniel J. Boorstin's The Creators, had significant water-damage on the last 100 pages.

This wasn't mentioned in the book's description, and although the book was a bargain, I still feel a tad ripped-off. It's always difficult to know what to do in these situations. One one hand, I want the seller to be aware that the book's condition wasn't described adequately, but on the other, I don't want a refund, as I want to keep the book.

UPDATE: I just opened J. R. Hale's Renaissance Europe 1480-1520 and heard (and felt) the spine crack as I did so. This will mean that the pages will eventually start falling out. It's a 1971 paperback, so it's not unexpected.

This wasn't mentioned in the book's description, and although the book was a bargain, I still feel a tad ripped-off. It's always difficult to know what to do in these situations. One one hand, I want the seller to be aware that the book's condition wasn't described adequately, but on the other, I don't want a refund, as I want to keep the book.

UPDATE: I just opened J. R. Hale's Renaissance Europe 1480-1520 and heard (and felt) the spine crack as I did so. This will mean that the pages will eventually start falling out. It's a 1971 paperback, so it's not unexpected.